On a monthly basis, we invite a guest author to contribute their voice in response to a specific article or video. This month's response was provided by Kelsey Woods. To read the article Kelsey is responding to, click here.

Screw finding your passion.

A response.

To get you up to speed, blogger Mark Manson tells readers to “screw finding [their] passion” because they shouldn’t have to look for it. If you don’t know what you love, and I mean feel it in your bones kind of love, you might be screwed.

To an extent, I agree. If you want a job that “doesn’t feel like a job”, that’s “fun” and “rewarding”, and that you “look forward to”, you need to find a career that is so true to who you are, you don’t know where the job ends and you begin – that’s real passion.

But… and here’s the but: you also need to be good at it, because that’s how you get people to pay you to do what you love.

I loved when Manson wrote of playing in the playground as a child, “Nobody told you to do it, you just did it. You were led merely by your curiosity and excitement.”

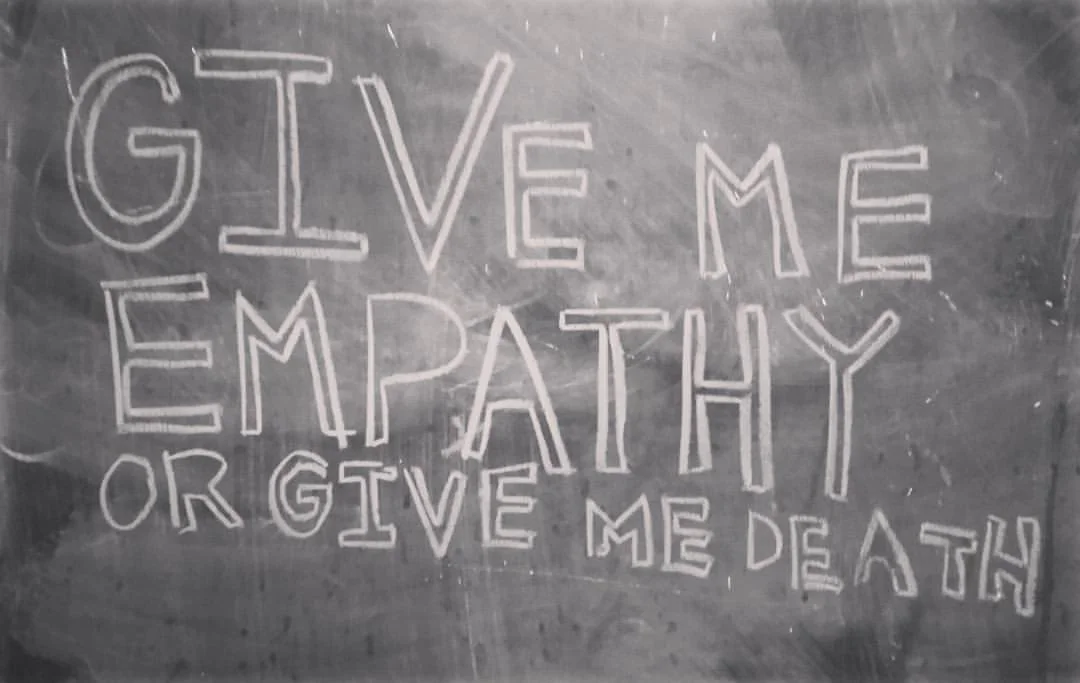

That’s how I feel about nonprofit development. No joke. My passion lies in the ideals of equity and social justice; it is grounded in the fundamental belief that all human lives have equal value and should have equal opportunity. That’s what lights my fire.

But my curiosity and excitement lie in the business side of things. I spent the first eight years of my professional career fundraising because I get my kicks from watching a bottom line grow and knowing how that will feed my passion. I get excited (yes, high fives all around kind of excited) when we add a staff person to our small team, not because my work load will decrease (it won’t), but because I can see how that will lead to long-term organizational growth, which yes – feeds my passion.

Manson goes on to say, “The problem is not a lack of passion for something. The problem is productivity. The problem is perception. The problem is acceptance.” He concludes by stating the problem is priorities, and in my experience, there is some real truth to that.

Just out of college I started my career in IT sales. Let’s be very clear here, I left the University of Washington with a theatre degree, and I decided to sell software licensing and server solutions to IT directors around the US. Because I totally knew what I was talking about. Right…

I knew I loved business development, and I really loved the idea of having some money to burn, but the thing is, that wasn’t enough. It turned out (for me at least) that if you don’t love IT solutions, you probably don’t know much about them and likely you aren’t too interested in learning about them, so you won’t be very good at selling them.

Back then, I had my priorities wrong. (again, not at all knocking people who love IT) but at 21, I thought I needed to have a certain type of career making a certain amount of money. It was safe, and nonprofits had a reputation for being, well…not that. So despite having spent my high school years running a student theatre company and educating my peers about HIV/AIDS, despite having served as the Philanthropy Chair in my sorority and participating in feisty political conversations with my peers throughout college, I took a job that would make me some money, and one that I could leave in the office at the end of each day.

My whole life I had been working toward the career I have now and I had no idea. It took losing my mom to breast cancer, and finding some real passion (read:anger) about that, to reprioritize and accept the vulnerability that comes with making your passion your career. Because when you do, that line you’ve drawn between yourself and your job becomes fuzzy, at best. Your work becomes personal, and that can be just as scary as it is rewarding.

So sure, screw finding your passion, because he’s right – it’s already there, you’ve found it. This is about choosing to do for a living, something that reflects your values and allows you to be that. And to be clear, it’s about being good at it, or getting good at it.